Baby Mother Rituals

What continued through this volatile period were gradual advances in food cultivation and animal domestication, along with growing knowledge of working metals. Many deep traditions tied to all forms of agriculture emerged, including the ‘sprouting mother’ and ‘baby mother’ rituals. Remarkably, these agricultural ceremonies have survived despite the complete disappearance of all other aspects of these most-ancient times.

Details may be found in their continued practice among Rural Clusters. The rudiments of several Tatchlan elements were also achieved, with the tentative communication with Cousins and the first modifications of other living beings. There is no reliable dating system for most of this time. Despite each of these falling to violence and destruction, they inspired later generations and planted the seeds of the current Cluster-of-Clusters perfection.

The walls of the Primary Mountain Circle were also a significant source of wealth. Azure Stone, almost unknown to the rest of Anu, was abundant throughout the Veradapandra Mountains on Statos-Vey. As it is now, Azure was listed as the First Grade of builder and sculptor stone, particularly those infused with veins of Argent, Cupric and Lapis minerals. All six classes of minerals and gemstones lay in abundance within the Veradapandras, where it is said that ‘the wealth of Anu is gathered.’ This was the second stabilizing foundation of the empire.

Founding of Bhampay

The Funomanru Dynasty also founded the first of many ocean ports in what would become the city of Bhampay. The first extensive and stable trade networks were established with Bhampay at their hub, bringing goods from all parts of Anu to benefit a burgeoning population. This led to an influx of populations from remote communities, many finding new homes in the port city. Children of distant principalities were also brought to Bhampay to be educated at the first universities alongside the empire's elite.

Most were explicitly trained as the ‘service aristocracy’ of the dynasty before being sent back to serve the designated governors of peripheral nation-states for the Funomanu dynasty. All these activities contributed to Bhampay's development of a unique cultural status.

Thithanu - the World City

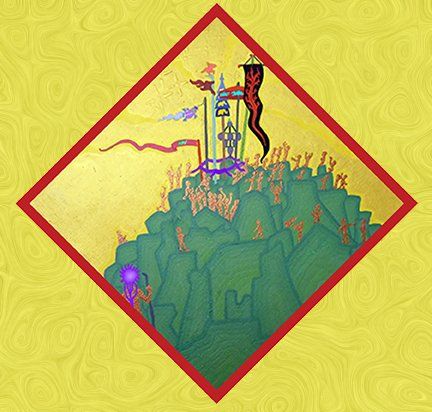

The Buyanupithar Dynasty was based in northern Rho-Jashun in their consolidated capital of Thithanu, close by the grand Mount Thuma with the immense Uthumpon River flowing around three sides. Due to the abundance of water from myriad small rivers and underground springs seeking out the Uthumpon River, Thithanu became the first known city dominated by an extensive canal system. (Bhampay on Statos-Vey had yet to divert the Siana River through the city). With Mount Thuma forming a dramatic backdrop to the north and the Uthumpon River creating the south, west and eastern boundaries, Thithanu became the largest metropolis on Anu, and an extensive road system converged on it from all sides. Not until the Living Mountains of the Koru during the Secondary Epoch were larger urban populations brought so closely together. This mighty urban centre would remain the capital throughout the Buyanupithar, Midin and Muraharoma Dynasties. Its name was a derivation of the words World City in the language of the time. It supported an immense population, saw many events, nurtured cultural and historical innovations, and authored innumerable masterpieces. Among many other recorded wonders, at this height, there were one hundred ‘North Towers’ encircling the southern surround of Mount Thuma.

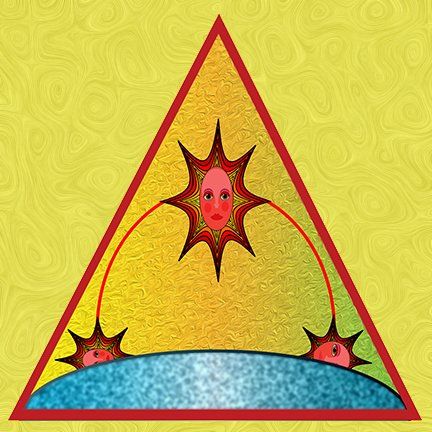

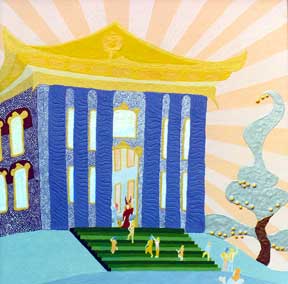

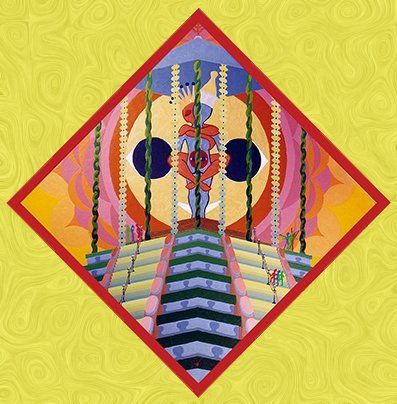

This Primary Epoch Icon is based on a most-ancient emblem recovered from the Mount Midin Amassment. It is estimated the original image dates from early in the Buyanupithar Dynasty. It shows a stylized Uthumpon flowing in its original course to the city's south. It is in the foreground, with Mount Thuma rising to the north behind it. The mountain is presented in an idealized form. The city appears as a series of perfect structures at the mountain's base. It is unknown whether these shapes had a specific symbolic significance at the time. This Icon can now Summon because it is a vital nursery for the first significant associations of Masters dwelling there. For centuries, they continued their work in the shadow of Mount Thuma before the Menem Priesthood drove them out.

Institutes Enumerator, Wellbeing and Preeminent Works Ministries

Previous unifying dynasties had seen fit to conduct a census and analyze the results. Still, this dynasty formalized the regular taking of the census each decade within the new ministry known as

Enumerator. They also added what would come to be known as the third of the ministry’s three bureaus, the

Erudite Bureau, to oversee and administer various intellectual and cultural activities. They also founded the

Wellbeing Ministry, which comprises three bureaus: the

Pacifier,

Ratio, and

Completion. While within the later

Cluster-of-Clusters Nation, two additional bureaus would be added; the original three parameters have remained unchanged through subsequent ages. This dynasty is also distinguished for creating a third ministry, that of

Preeminent Works. The four bureaus of today’s ministry were all founded at this time. The catastrophic failure of the great city of

Thithanu to control its growth and sufficiently deal with its unhealthy conditions was fresh in the minds of many. The newly instituted Preeminent Works Ministry was tasked with massive infrastructure works to make

Bhampay and other places of health and beauty. These many initiatives were, in part, a response to what was seen at the time as the foul and dour nature of the former capital of Thintlith under the influence of the

Menem priesthood.

Masters receive warning of Suvuka

The Mount Uluvatu Masters on Statos-Vey received many warnings. These included news of increased disturbance incidents, such as a rise in Gandahatapan and Mahakram insect wars. Such natural anomalies were followed by explicit dispatches from their serving Cousins and Krall of an imminent threat approaching from Northern Rho-Jashun. They relayed this to their Tatchlan compatriots in Thithanu, who began to sound the alarm. Gradually, other authorities in various fields saw the signs and joined their call. Only a fraction of the population chose to listen and begin to move south ahead of the approaching storm. It is noted that while the Muraharoma emperor Semesilian XIII struggled with conflicting reports and indecision in Upata-Shepsus on Statos-Vey, he did accede to the Master’s urgings to stop all emigration from Statos-Vey to Rho-Jashun and to begin to fortify the three gaps in the southern Mulungu Mountain range. Due to trade and other issues, barriers had already been raised at these locations over a century earlier.

The above image is a common feature in most Koru Living Mountains during the Secondary Epoch. They are crafted mainly by taxidermists using recovered bones and other materials, mostly from the northern shores of the Huallapandu Headlands.

Uthumpon River assaulted

Such was the rage of the Suvuka when they arrived at Thithanu; they changed the course of the mighty Uthumpon River. Were the evidence not irrefutable, it would be impossible to credit. They did so by tearing down this immense city and pushing most of the ruin into the river in such quantities that it could no longer flow and change course. With all hope lost, the surviving Tolku began a frantic evacuation south across the Marachla Plain. Those reaching safety said the Suvuka became intent on levelling the World City and did not follow them initially. Due to many topographical factors, the river backed up and flooded broad areas, presenting something of a barrier when the Suvuka began to give chase. Despite these watery impediments, they quickly overtook more than half of the refugees and destroyed them. The miserable remnant allowed through the Xaduron Wall of The Impenetrable Barrier Region was the last Tolku of Rho-Jashun. The Uthumpon River eventually forged a new channel. It now flows far north of Mount Thuma and its small companion, Mount Thanur. This is the only example of such a monumental alteration of a major river by the Suvuka.

Suvuka convert Menem Shrines

There was one mysterious exception to their programme for eradicating all signs of Tolku presence on Rho-Jashun. Forty-four Menem shrines were built across Rho-Jashun, and a further twenty were built on Statos-Vey. These are mentioned in the Menem religious text, the ‘Daruadunnal,’ within the set of martial tales known as ‘The Tarunachit.’

They supposedly contained relics of the war between the Menem and Kovlah in Ranvartawan. They were characterized as having an egg-shaped central depository of the relic surrounded by large curving walls with elaborate murals depicting aspects of the Menem narrative. The Suvuka chose to trample down the complex while carefully converting these forty-four sites into their Running Rounds, suggesting something about these structures and their locations separated them from all others. Many theories have been expounded, but no clear answer to this mystery has gained acceptance.

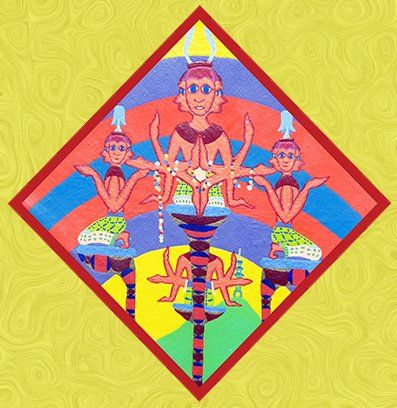

From the inner surface, four groups of three Memanu grow inwards towards Nu, symbolizing the Memanu's role in sending messages from one side of the inner sphere to the other. Their blossoming tops are presented as stylized swirls. Between them stand what appear to be four large, three-tiered altars with a flame coming out of the top portion. It has been speculated the lower tier represents rock and soil, and the middle story, which appears to be a stylized wave, is meant to symbolize Anu’s oceans. By this estimation, the upper level is the sky, and the flame is Nu himself. Eight tiny figures stand on each of these structures with their hands joined above their heads. A single Xumkuka flies over this architectural arrangement.

They worshipped and feared the soil and were told to always ‘tread lightly’ on it. They treated the two Skin Banes, Consumption Monoliths and Hungry Rock, as ‘Anu Gateways’ and were known to ceremonially ‘feed’ them with stone refuse to fortify the Skin of Anu ceremonially. Anu quakes were monumental traumas for them, and elaborate rituals and ceremonies attempted to mitigate them. Eruptions of Dead Blood horrified them, as they believed this was puss issuing from a wound in the Skin of Anu. Despite the tradition being extinct, some agricultural practices, including the ‘Baby Mother’ harvest rituals, come down to us from this time.

Yeoyupan Mystery

Given its confirmed early date of composition, it also poses a puzzle. Before Zitapermas, there had been no other mention of the

Suvuka within any other surviving

Menem or literature. Until the

First Suvuka Onslaught, little was known about them. Many shipping losses crossing the

Panchala Sea led to a tradition of evil ‘residing in

the North.’ Increasing reports of fantastic bones washing up on the northern shores of

Rho-Jashun cemented this notion. When the first explorers successfully returned to Rho-Jashun and described the Suvuka, the Menem Priesthood condemned them for suggesting such a being existed (not being mentioned in the

Daruadunnal and other now lost early texts). They attempted to prohibit and destroy their published accounts (this is why the Zitapermas were also initially suppressed), declaring they fell under interdicts against all forms of ‘Kovlah Heresy.’

While its structure and language usage prove this epic significantly predates the Furrumittal collection, it describes the landscape of Thermistal with surprising accuracy. The unknown author(s) also possessed a comprehensive knowledge of the rest of Anu, along with many long-extinct mythologies. With few exceptions, the only other surviving source of information about them is the Everlasting Ennui, dating a millennium in the future of The Lesser Era. Traditional Menem works eschewed all such religions, claiming they were evil falsehoods of Yeoyupan and later fabrications of the Kovlah/Suvuka. Lastly, Suvuka’s social structure and many dancing and running rituals are described in detail, as could only come from first-hand observation. Many questions remain unanswered about how this work fits with what is known of the period.

All of this evidence now leads Venerable Scholars to conclude this creative work was the product of an anonymous author, or authors, who had survived one or more extended voyages to what was then known as the ‘Dark Continent.’ It has been suggested, given the poor reception factual accounts had in Thithanu, that the dramatist chose to frame their message as a theatrical narrative to increase the likelihood of its survival. Several forensic examinations were undertaken, by notable academic figures, of other literature surviving from the time to identify the playwright - without success. Such is the enduring popularity and profound respect accorded to this work that, even today, contentious debates erupt occasionally within learned circles and at assemblies over various points on interpretation and authorship of this most-ancient narrative.